The Future Is Organic by Dr Charles Merfield

“As a philosophy and a values-based ethical system, organics can’t be unscientific, as it is impossible for any value system to be either scientific or unscientific.”

The pros, cons and even validity of growing organically have been much debated, and lines were drawn in the soil long ago. Yet, the science is clear that it is the only sustainable path forward.

First published in NZ Gardener Magazine - May Edition, re-published with permission on www.oanz.org.

In 2011, the late Sir Paul Callaghan – award-winning Kiwi physicist specialising in nanotechnology and magnetic resonance – said, “Putting aside the paradox of organic farming, unscientific to the core that it is, the rest is an absurd list.”

That these kinds of beliefs are still held today, especially among highly regarded scientists, is disappointing as they fly in the face of the facts.

Organic farming and gardening is more than a century old. It was part founded by scientists, is practiced on some 72 million hectares globally representing 1.5 per cent of farmland, with tens of thousands of scientists, including many professors, researching and teaching organics, publishing in scientific journals and belonging to organic scientific societies.

Why therefore are some scientists (and non-scientists) at loggerheads over the scientific validity of organics?

What is organic?

Fundamentally organics is a philosophy: a worldview of how farming and gardening “should” be done; that is, the “right” way to farm and garden.

As a philosophy and a values-based ethical system, organics can’t be unscientific, as it is impossible for any value system to be either scientific or unscientific. This is where Sir Paul’s mistake lies. To quote an even more famous physicist, Wolfgang Pauli, the charge that organics is unscientific is “not even wrong”, because the charge utterly confounds two incompatible domains of human knowledge: ethics and the scientific method – it is a “category error”.

Scientific method – doing experiments – cannot answer an ethical question. For example, it is impossible to design an experiment to decide if murder or slavery is right or wrong.

Science, and therefore scientists (speaking as scientists not as citizens), therefore have zero authority on matters of right and wrong. That is why we have democracy, because if science could decide ethical questions, we would not need politicians. An analogy to illustrate the error is that nuclear weapons are clearly scientific as their conception and creation requires quantum mechanics, the most profound science of our age. However, the decision to use, not use, or even build and possess nuclear weapons is clearly not a scientific decision. It is an ethical and political decision. No-one decries the non-use of nuclear weapons as being unscientific. Indeed, the statement is patently absurd.

So the claim that the non-use or prohibition of some forms of scientific technology (agrichemicals, genetically engineered organisms) is unscientific, is likewise patently absurd. All forms of agriculture are fundamentally political, ethics- and values-based. To call any of them scientific or unscientific is a complete error.

How does science relate to agriculture?

Methods of agriculture can be classed as being scientifically informed – they use scientific knowledge to inform their philosophy. For example, there is a huge amount of scientific information about the harm done to people and our planet from agricultural technologies such as nitrogen fertilisers, pesticides, cultivation and monocultures. Organics takes this information and decides to limit or prohibit the use of these technologies due to the harm they cause.

The alternative to science-informed farming and gardening can be described as theological agricultures, which at their core are informed by things such as spiritual and cultural beliefs. For example, biodynamic farming and gardening is based on the spiritual teachings of Rudolf Steiner, which are outside the realm of science.

Likewise, in the US, the Amish’s farming practices are all determined by their religious beliefs. For many indigenous peoples, there is no separation between their religious and spiritual beliefs, their day-to-day culture (unlike in the West where religion and culture are often disconnected) and their farming and gardening practices, so these can be classed as theological farming systems.

Organic farming and gardening is, therefore a science-informed farming system.

“Organics is an ecologically based farming and gardening system. Conventional gardening and farming is not – it is a reductionist system.”

How does this affect the home gardener?

First and foremost, you need to manage the garden as an ecosystem, as that is what it is. Ecology is the science of how species interact with their non-living environment such as soil and climate, and also other species. It is therefore a system level science, and to be an effective ecologist you need to think holistically or at a system level: how all the species in your garden interact with each other and their environment. This allows you to manage the different species (all species, not just plants) in your garden’s ecosystems to achieve your desired outcomes.

Organics is very much an ecologically based farming and gardening system. Conventional gardening and farming is not – it is a reductionist system.

The first rule of ecosystems is biodiversity. Conventional or intensive farming and gardening is dominated by monocultures – fields of crop plants and nothing else. These are ecological deserts – they lack diversity and are consequently ecologically unstable. Pests, diseases and weeds want to invade them so that as soon as people stop managing them, nature re-establishes biodiversity.

Ecological science has clearly shown the many benefits of biodiversity, including increased yield, improved soil health and water storage, lower pests, diseases and weeds, more beneficial insects, better overall resilience and stability. This is contrary to the teaching of conventional farming and gardening, but the science is clear: the ecologists are right and the conventional agronomists are wrong; biodiversity is the answer.

Organic rules have banned synthetic pesticides, such as glyphosate (Roundup) and methiocarb (slug pellets), so organics use biodiversity to help manage pests, diseases and weeds. For example, having a diversity of plants provides food, such as nectar and pollen, and shelter for beneficial insects such as carabid beetles, hoverflies, ladybirds, lacewings and parasitoids which attack pests and in most situations will keep their populations low enough that they don’t cause harm.

Ecology calls this dynamic balance; nothing is ever static in ecology and there is constant churn of species. At times, some species increase in number, but then they run out of food or their predators attack them, and their populations decline again.

This idea of dynamic balance is a key concept for organic gardening. A few aphids on your roses are not going to harm them, but millions of aphids will. If you have dynamic balance in your garden, it is likely that pests (aphids on roses) will appear, but pretty soon, their predators will find and eat them.

“Lots of scientific experiments show pesticides often make pests worse by eliminating natural enemies.”

This is why it is important not to panic and spray the second you see a few pests but, to wait to see if their natural enemies keep them below problematic levels.

If you spray the pests as soon as they first appear, you remove the predators’ food and likely also kill the predators, so when the pests come back, there are no predators to attack them, so their populations explode. This is one of the ironies of pesticides. Lots of scientific experiments show pesticides often make pests worse by eliminating natural enemies.

How biodiverse are our gardens?

A lot of the time, our flower borders have good biodiversity in them, especially if you have a cottage garden approach where you mix up lots of different plant species. Where gardens often lack biodiversity is in the vege patch and the lawn.

In the pre-herbicide era (before the 1940s), clover was considered a highly valuable lawn plant. People paid top dollar for lawn seed with lots of clover in it. Now we spend lots of time and money on herbicides to kill clover, and, any non-grass, in our lawns. Why? Clearly, it’s a matter of aesthetics, but fashions change.

When I last resowed my lawn, I deliberately mixed small-leaved white clover in with the grass, as I’m a tight-wad and I don’t like paying for nitrogen fertiliser when I can get it for free from clovers. Their flowers also provide nectar and pollen for bees and other beneficial insects. I also love the beautiful flowers on dandelions and daisies that have made their home in my lawn, which also tells you I don’t cut it to within an inch of its life twice a week. In my view, lawns should be left long, so they can flower and provide nectar and pollen to beneficial insects that attack crop pests, and look pretty, and save all that time and petrol wasted on frequently mowing them. That is an organic approach.

Turning to the vege plot, a lot of the time we mimic conventional farming in that we have monocultures of crops in our vege beds. Why?

In conventional farming, there are some practical reasons – large amounts of each crop planted and harvested to a strict schedule to keep shop shelves well stocked.

At home, we want small amounts of produce at a time: an onion, some potatoes and some salad for dinner. Intercropping is an organic technique where different plant species are planted together. In the home garden where we are typically harvesting a few plants at a time for dinner, where a plant is removed just replant something else in the gap that is left.

Again, the science is clear. You can massively increase the amount of produce per square metre using this approach, not only because you are making the best use of space, but, the interactions among the different plant species can boost their growth, and, by mixing things up, it becomes harder for pests and diseases to run rampant through your crops, and by keeping soil covered you block out weeds.

Build your foundation

Soil health is the issue on which organic farming and gardening was founded: Agriculture should sustain and enhance the health of soil, plant, animal, human and planet as one and indivisible. This is based on our scientific understanding of how the planetary systems work.

Soil is the foundation for life on land. It’s the medium in which (most) plants grow, and plants are the powerhouses of life as it is only they that capture the sun’s energy, which is then used by all other life forms. Soil is also the most complex ecosystem on the planet, and there are billions of organisms and millions of species in just a teaspoon of soil, far more than even a tropical rainforest.

Yet conventional farming and gardening often treat soil like dirt, considering it as only a medium to keep plants upright and applying soluble fertilisers to directly feed crop plants, without taking into consideration all the other species in soil that also need to be fed. The result of this is clearly demonstrated by scientific research: globally, many of our soils are highly degraded, some 15 per cent to the point that they can no longer grow crops.

While soil is incredibly complex, maximising soil health is surprisingly easily. Maximise the biodiversity of plants growing in any one piece of soil. Keep soil covered by living plants as much of the time as possible. Maximise the return of organic matter to the soil by mulching and applying compost. Avoid compacting the soil through walking and driving on it. Minimise or eliminate cultivation – go no-dig. Make sure nutrient levels are at optimum. Just these six actions are all you need.

You don’t need to buy inoculants or fancy potions to boost soil health, a biodiversity of living plants and not physically harming soil is all you need. The worst thing you can do to soil is leave it bare, without living plant cover.

So, gardening organically is not only clearly based on science, it is also clearly the kind of gardening that is required if we are to address the multiple, interlinked planetary crises, such as climate change, biodiversity loss and nutrient and pesticide pollution.

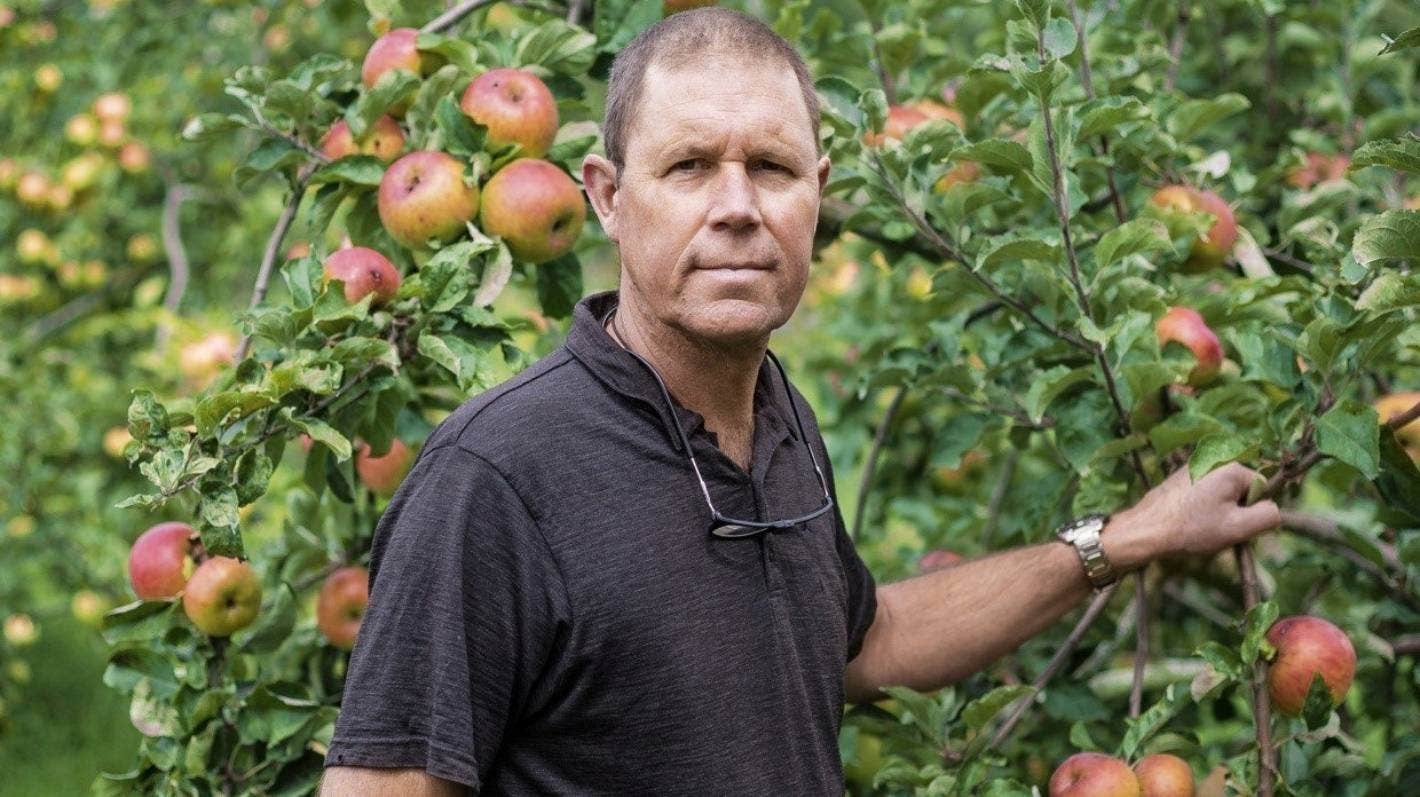

CHARLES MERFIELD has been involved in organics for over 30 years, as both a grower and scientist. He is the head of the BHU Future Farming Centre and a member of OANZ’s Advisory Board.